Do All Mammals Have Hair?

Yes, virtually all mammals possess hair at some stage of their lives, making it a defining characteristic of the class Mammalia. While some, like whales or elephants, appear hairless, they typically have hair during embryonic development or retain sparse, specialized hairs as adults. This remarkable feature plays crucial roles in insulation, protection, and sensory perception across the incredibly diverse mammalian kingdom.

Have you ever looked at a fluffy kitten, a majestic lion, or even your own arm and pondered the sheer ubiquity of hair in the animal kingdom? It’s a fascinating feature, often taken for granted, but deeply ingrained in what it means to be a mammal. We see fur, wool, spines, and bristles everywhere we look, leading many to assume that all members of the Mammalia class are covered head to toe in some form of hair. But is this truly the case? Do all mammals have hair?

It’s a question that sparks curiosity and often leads to surprising answers. While the image of a furry creature is almost synonymous with “mammal,” the reality is a little more nuanced than a simple yes or no. Prepare to dive into the amazing world of mammalian hair, exploring its incredible diversity, its vital functions, and the fascinating “exceptions” that prove the rule in unexpected ways. Get ready to challenge your assumptions and discover just how truly remarkable this defining characteristic of mammals really is!

Key Takeaways

- Universal Trait: Hair is a defining characteristic of mammals, present in virtually all species at some point in their life cycle, even if only during embryonic development or as vestigial hairs.

- Diverse Forms and Functions: Mammalian hair varies greatly in density, length, and type, serving multiple purposes such as insulation, protection (camouflage, defense), sensory perception (whiskers), and social communication.

- “Hairless” Exceptions Aren’t Truly Hairless: Mammals often perceived as hairless, like whales, dolphins, elephants, and rhinos, still possess hair. Whales have it in embryonic stages, while elephants and rhinos retain sparse body hair.

- Insulation is Key: One of the primary evolutionary drivers for hair development was thermoregulation, helping mammals maintain a stable internal body temperature in various environments.

- Beyond the Coat: Specialized hairs like vibrissae (whiskers) are vital sensory organs, enabling mammals to navigate, hunt, and interact with their surroundings, even in darkness.

- Evolutionary Significance: Hair is an ancient mammalian innovation, dating back millions of years, crucial for the survival and diversification of mammals across Earth’s diverse ecosystems.

📑 Table of Contents

The Defining Trait of Mammals: Hair

Let’s cut right to the chase: the short answer to “do all mammals have hair?” is a resounding yes – with an important asterisk. Hair is, in fact, one of the most fundamental and defining characteristics of mammals. Along with mammary glands (which give the class its name) and three middle ear bones, hair is what sets mammals apart from all other animal groups. It’s a hallmark of our lineage, present in almost every single species, even if it’s not immediately obvious.

What is Hair Anyway?

Before we explore its presence, let’s understand what hair actually is. Hair is a filamentous epidermal outgrowth composed primarily of a tough, fibrous protein called keratin. It grows from follicles embedded in the skin. Think of your own hair, or a cat’s fur – it’s all built from the same basic stuff. This keratin structure makes hair strong, flexible, and relatively lightweight, perfect for a multitude of biological roles.

The key here is that while hair can be incredibly diverse – from the soft down of a newborn to the stiff quills of a porcupine – its underlying structure and origin are consistent across mammals. So, whether it’s thick, thin, long, short, bristly, or silky, if it’s made of keratin and grows from a follicle in the skin, it’s hair!

Not Always Obvious: The “At Some Point” Clause

The crucial part of our “yes” answer is the phrase “at some point in their lives.” Many mammals that appear to be hairless as adults actually possess hair during their embryonic or fetal development. This developmental stage is critical because it shows the genetic blueprint for hair production is present and active, even if the hair is later shed or becomes incredibly sparse. It’s a reminder that evolution often leaves traces, even when a trait is no longer the primary focus in adulthood.

For example, take humans. We’re often called “naked apes” because we have significantly less dense body hair compared to most other mammals. Yet, we are born with a fine, downy hair called lanugo, which often sheds before or shortly after birth. And of course, we retain hair on our heads, in our armpits, and in other areas throughout our lives. So, while we might not be as conspicuously furry as a bear, we definitely fit the bill.

From Fur Coats to Sparse Strands: The Incredible Diversity of Mammalian Hair

The variety of hair types and distributions among mammals is truly astounding. It reflects millions of years of adaptation to vastly different environments and lifestyles. This diversity is a testament to hair’s versatility and evolutionary success.

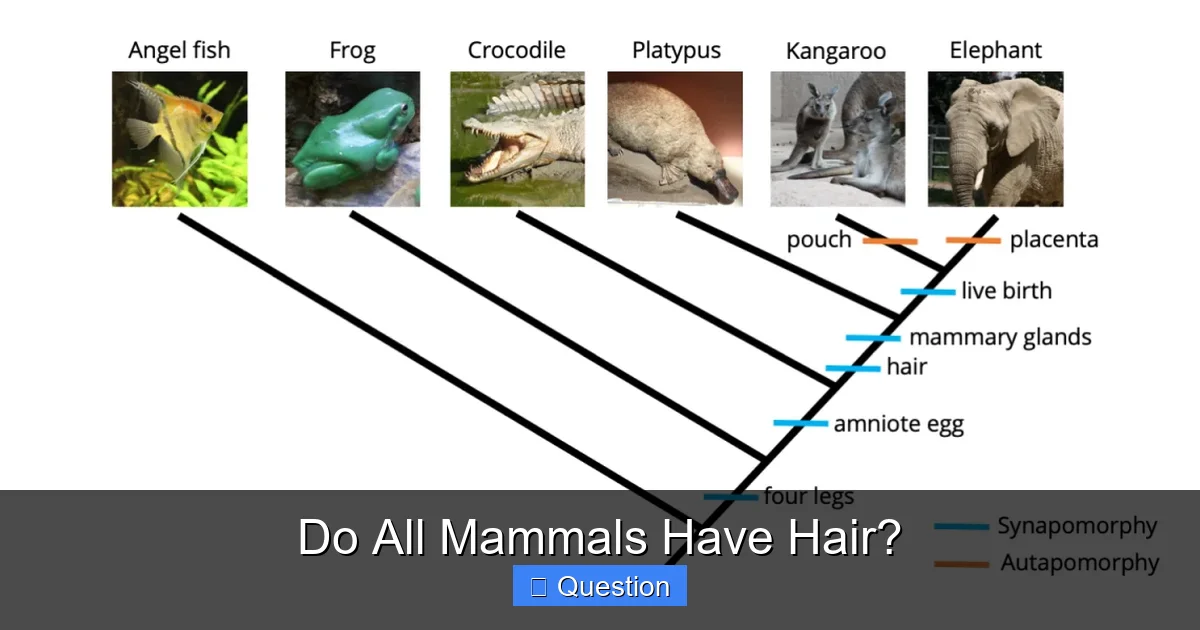

Visual guide about Do All Mammals Have Hair?

Image source: medshun.com

Thick Fur and Wool

When most people think of mammalian hair, they probably picture a thick, insulating coat. Animals living in cold climates, like polar bears, arctic foxes, and musk oxen, have incredibly dense fur designed to trap air close to the body, providing exceptional insulation against freezing temperatures. This fur often consists of two layers: a soft, dense undercoat for warmth and longer, coarser guard hairs that protect against snow, rain, and wind.

Sheep’s wool is another famous example of specialized hair. Its crimped fibers create air pockets, making it an excellent insulator, which is why it’s been prized by humans for centuries. Similarly, beavers and otters have incredibly dense, waterproof undercoats that keep them warm and dry even when submerged in icy water.

The Naked Truth? Sparse Hair Examples

On the other end of the spectrum are mammals with very sparse or seemingly absent hair. But even these creatures typically retain some form of hair, often in specialized locations or as fine, scattered strands. Consider animals like the naked mole-rat. Its name suggests a complete lack of hair, but if you look closely, you’ll see fine bristles scattered across its body. These aren’t for warmth (it lives underground in a stable temperature), but rather act as sensory aids, helping it navigate its dark tunnels.

Similarly, certain breeds of domestic animals, like the Sphynx cat or various “hairless” dog breeds (e.g., Chinese Crested, Xoloitzcuintli), have been selectively bred for minimal hair. However, even these animals are not truly hairless; they usually possess a fine, peach-fuzz-like covering or sparse hairs in specific areas, showcasing that the genetic machinery for hair is still very much present.

Specialized Hairs: Whiskers, Spines, and Scales

Hair isn’t just for covering the body; it can also be highly specialized for unique functions. Take vibrissae, commonly known as whiskers. These stiff, sensitive hairs found on the faces of many mammals (cats, dogs, seals, rats, etc.) are deeply rooted and connected to a rich supply of nerves. They act as crucial sensory organs, helping animals navigate in the dark, hunt, assess openings, and perceive their surroundings through touch and air currents. Without whiskers, a cat would be significantly hampered in its ability to move and hunt effectively.

Porcupines and hedgehogs have modified hairs that have evolved into sharp, protective spines or quills. These are essentially hardened hairs designed for defense, deterring predators with their painful barbs. Pangolins, unique scaly mammals, have scales made of keratin – the same protein that forms hair and fingernails – though they are structurally different from typical hair follicles. Still, pangolins also have sparse, stiff hairs between their scales, especially when young.

Why Hair? The Many Functions of a Mammal’s Coat

The widespread presence and incredible diversity of hair in mammals point to its immense importance. Hair isn’t just an aesthetic feature; it serves a multitude of vital biological functions that have been crucial to mammalian survival and success.

Insulation and Thermoregulation

Perhaps the most well-known function of hair is insulation. By trapping a layer of air close to the skin, hair helps mammals maintain a stable internal body temperature, regardless of external conditions. This ability, called thermoregulation, is a hallmark of warm-blooded animals and allows mammals to thrive in environments ranging from scorching deserts to frozen polar regions. Animals like Arctic foxes can survive incredibly low temperatures thanks to their thick, insulating fur, while others, like camels, use sparse, reflective hair to reduce heat absorption in hot climates. Hair helps keep heat in when it’s cold, and in some cases, can even help deflect heat when it’s hot.

Protection: Camouflage, Defense, and Physical Shielding

Hair offers various forms of protection. Its most obvious role is as a physical barrier against the elements – sun, wind, rain, and minor abrasions. Beyond that, hair provides excellent camouflage. The spotted coat of a leopard, the striped pattern of a tiger, or the dappled fur of a deer all help these animals blend seamlessly into their surroundings, either to ambush prey or to avoid becoming prey themselves. Seasonal changes in coat color, like those seen in snowshoe hares or arctic foxes, further enhance this protective camouflage.

As mentioned with porcupines, hair can also be modified into formidable defensive structures. Even less dramatic hair can deter parasites and provide a layer of defense against insect bites and minor scratches.

Sensory Perception

We’ve already touched on whiskers (vibrissae), but it’s worth reiterating their importance. These specialized hairs are touch receptors, allowing mammals to “feel” their environment without direct contact. They are particularly crucial for nocturnal animals, those living in confined spaces (like burrows), or aquatic mammals navigating murky waters. The slight deflection of a whisker can send precise information to the brain about obstacles, air currents, and even the texture of objects, acting as a crucial sixth sense.

Social Signaling and Communication

Hair also plays a role in social interactions. The mane of a male lion signals strength and dominance. The piloerection (raising of hair, like a cat fluffing up or a dog raising its hackles) in many mammals can signal aggression, fear, or a desire to appear larger and more intimidating. The vibrant colors and patterns in the fur of some primates can be used for species recognition and mate attraction. Even the condition of an animal’s coat can signal its health and fitness to potential mates or rivals.

The Curious Cases: Mammals That Appear Hairless (But Aren’t Really)

This is where the “all mammals have hair” question gets particularly interesting, as it challenges our visual perception. Many animals that seem to lack hair entirely still hold onto this mammalian trait in some form.

Whales and Dolphins: A Hairy Past

Perhaps the most famous “hairless” mammals are cetaceans – whales and dolphins. When you picture a sleek dolphin or a massive blue whale, you don’t typically imagine a furry creature. However, if you look at whale embryos, you’ll find they are covered in fine hair, particularly around the snout. This hair is usually shed before birth or shortly after, as it would create drag and hinder their aquatic lifestyle.

Despite appearing hairless, some adult cetaceans do retain a few vestigial hairs. For instance, many baleen whales, like the Humpback, have sparse hairs around their blowholes and mouths, which are thought to be sensory, helping them detect prey or navigate. This embryonic hair and the occasional adult remnants are strong evidence of their mammalian heritage and shared ancestry with land-dwelling, furry mammals.

Elephants, Rhinos, and Hippos: Sparse but Present

These majestic giants of the land also give the impression of being mostly hairless, sporting thick, wrinkled skin. Yet, if you get up close, you’ll see that they are not entirely bare. Baby elephants, for example, are born with a surprising amount of bristly hair, especially on their backs and heads, which thins out considerably with age. Adult elephants retain sparse, coarse hairs scattered across their bodies, particularly on the tail, around the head, and on their backs. These hairs are thought to help with touch sensitivity, insect deterrence, and even heat dissipation.

Similarly, rhinoceroses and hippopotamuses have very sparse body hair. Rhinos have thick skin and a few stiff hairs around their ears, eyes, and tail. Hippos are known for their mostly smooth skin, but they do possess fine, almost invisible hairs scattered across their bodies and more prominent bristles on their snouts and tails. In all these cases, the hair is reduced because their large body size and thick skin are sufficient for thermoregulation, and a dense fur coat would actually hinder heat dissipation in their warm environments.

Humans: The “Naked Ape” Paradox

As mentioned earlier, humans are often considered relatively hairless compared to our primate cousins. While we don’t have a thick coat of fur, we are far from hairless. We possess hair follicles covering almost our entire body, with the exception of the palms of our hands, the soles of our feet, and a few other small areas. Most of this body hair is fine, short, and lightly pigmented (vellus hair), making it less conspicuous than the terminal hair on our heads, eyebrows, or pubic regions.

The evolutionary reduction of body hair in humans is a topic of much scientific debate, but it’s generally thought to be linked to thermoregulation in hot, open environments where early humans hunted. Less hair allowed for more efficient sweating and cooling. Despite this reduction, our continued presence of hair, in all its forms, firmly places us within the “all mammals have hair” category.

The Evolutionary Journey of Mammalian Hair

The story of hair isn’t just about what it does for individual mammals today; it’s also a deep dive into the evolutionary history of an entire class of animals. Hair didn’t just appear overnight; it evolved over millions of years, proving to be a highly adaptive trait.

Ancient Origins

Hair is believed to have originated in the earliest synapsids, the ancestors of mammals, over 300 million years ago. Fossil evidence, though indirect, suggests that these early mammal-like reptiles likely developed some form of integumentary covering, which eventually evolved into true hair. The evolution of hair was a crucial innovation because it provided a significant advantage: the ability to regulate body temperature. This allowed early mammals to become endothermic (warm-blooded), maintaining a stable internal temperature independently of their environment. This was a game-changer, enabling them to be active at night or in colder conditions when their cold-blooded reptilian relatives were sluggish.

Adaptation and Survival

Once evolved, hair diversified rapidly, adapting to countless ecological niches. From aquatic environments to arid deserts, from arboreal canopies to subterranean tunnels, the variations in mammalian hair helped different species thrive. It allowed for greater metabolic efficiency, better protection, and enhanced sensory capabilities, all contributing to the incredible success and radiation of mammals across the globe. The presence of hair, in some form, in almost every mammal alive today is a testament to its fundamental importance in the mammalian blueprint for survival.

Conclusion

So, do all mammals have hair? The answer, as we’ve explored, is a resounding yes, but with a crucial understanding of what “having hair” truly entails. It means that whether they are born with a full, fluffy coat, develop hair in the womb only to shed it, or retain just a few sparse, specialized bristles, the genetic legacy of hair is present in virtually every single mammal on Earth.

From the luxuriant fur of a snow leopard to the almost invisible strands on an elephant, from the sensory whiskers of a seal to the defensive quills of a porcupine, hair is a remarkably versatile and vital part of mammalian biology. It’s a trait that has enabled mammals to conquer nearly every ecosystem on the planet, providing insulation, protection, sensory perception, and even a means of communication. The next time you see any mammal, take a moment to appreciate this universal, yet incredibly diverse, feature – a true hallmark of our remarkable class.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are there any mammals that are completely hairless, without any hair at any point in their lives?

No, there are no known mammals that are completely hairless throughout their entire life cycle. Even species that appear hairless, like whales, typically have hair during their embryonic development. This highlights hair as a defining, universal characteristic of the mammalian class.

Why do some mammals have very little hair, like elephants or hippos?

Mammals like elephants and hippos have evolved to have very sparse hair primarily for thermoregulation in hot climates. Their large body size and thick skin are efficient at retaining heat, so a dense fur coat would cause overheating. Reduced hair allows for better heat dissipation and cooling.

Do humans count as having hair, given our relatively “naked” appearance?

Yes, humans definitely count as having hair. Although we have significantly less dense body hair compared to most other mammals, we possess hair follicles across most of our body and retain prominent hair in areas like our heads, eyebrows, and armpits. We also have fine vellus hair covering much of our skin.

What is the primary function of hair in most mammals?

The primary function of hair in most mammals is insulation and thermoregulation. Hair helps to trap a layer of air close to the skin, which prevents heat loss in cold environments and can also help reflect heat in hot ones, allowing mammals to maintain a stable internal body temperature.

Are whiskers considered hair? What is their function?

Yes, whiskers (or vibrissae) are specialized hairs. They are thicker, stiffer, and more deeply rooted than typical body hair, with a rich nerve supply. Their primary function is sensory perception, acting as touch receptors that help mammals navigate, detect obstacles, hunt, and explore their environment, especially in low light.

How did hair evolve in mammals?

Hair is believed to have evolved in early synapsids, the ancestors of mammals, over 300 million years ago. Its evolution was crucial for the development of endothermy (warm-bloodedness), providing insulation that allowed these ancient creatures to maintain a stable body temperature and be active in a wider range of conditions than their cold-blooded counterparts.